Mt.

Washington, 2003

Photos: Hank Schiffman. Click on any picture for a larger view.

Our story begins with an introduction by John Zenkus: Why Mt. Washington? George Mallory’s response to questions regarding his attempt to be the first person to reach Mount Everest’s summit was succinct and simple: “Because it is there.” In the world of cyclists, there are those who seek out climbs that others avoid, and if you are such a cyclist, there is one mountain that stands above them all—Mount Washington. But why Mount Washington? Alpe d’Huez is certainly more famous. Other European high Alpine passes will take longer to climb. Even in this country there are climbs with greater elevation gain. Why then, do 600 cyclists each year donate $300 for the experience to race up Mount Washington? The answer is more complex than “because it is there.” It is not the longest climb, the steepest climb, nor the climb with the greatest elevation gain. It is simply the climb that is the steepest for the longest distance. Couple this with above timberline scenery that is unworldly and weather that is unpredictable and you begin to understand Mount Washington’s attraction to cyclist climbers. Rightfully, Spain’s Angliru is feared for its steepness. But the Angliru is only very steep for 3 miles; yes, a bit steeper than any 3 miles on Mount Washington, but overall a 9.9% average grade. Mount Washington is very steep for almost 8 miles; overall a 12% average grade. In English, Mount Ventoux translates to “windy mountain;” Mount Washington recorded the highest wind speed ever recorded on the Earth. Italy has its Mortirolo, mountain of death; 124 persons to date have died on Mount Washington. Overall steeper than the Angliru, windier than Mount Ventoux, deadlier than the mountain of death; this is why for cyclists, Mount Washington stands above all other climbs. It is not hard just because it is steep. It is also windy and cold enough to be dangerous. Thankfully, with the correct gearing the steepness can be handled, albeit slowly, and in the summer time, on the toll road, racers really don’t have to worry about exposure, at least until the summit but there the race organizers always provide racers blankets. However, there remains one factor racers can never prepare for, the wind. As we shall see, after being absent the last few years, Mount Washington’s winds returned this year with a vengeance.

|

August 16, 2003. The starting line at

the base of Mt. Washington (situated in Eastern New Hampshire near Maine,

some 380 miles from NYC

by car). The temperature: 78–80 degrees with mild winds. These

racers face 7.6 miles to the top with 4,727 vertical feet of elevation

gain. Among the

starters was NYCC member Paul Spraos,

who tells

of

his

race: "The

winds began to blow strongly at around mile 3. By mile 5 1/2 we were

in the

clouds and buffeted by increasingly strong winds. For the last two

miles, visibility was 20–30 feet, except if your glasses misted

up as mine did, in which case it was virtually zero. The winds were

coming

from the side most of the time and grew stronger as you neared the

top. Fighting the cross winds was very, very difficult and I saw numerous

riders get blown off their bikes. The victims of the wind included

the winner of the women's race, Genevieve Jeansen."

Paul crosses the finish line on foot. What happened? In

his own words: "The

last 100 yards of the race has a 22% grade. Under the best of circumstances,

this is

a tough section. But after climbing almost a vertical mile, with

a wet road surface and with cross winds that the weather station

on the top of the mountain said were 60mph, I became one of its victims.

With my gas tank on empty, I had no energy to fight the wind and

it knocked me sideways. Then I found myself heading downhill. A spectator

at the side of the road stopped me from falling and I unclipped.

It's impossible to remount on that kind of grade, so I had no option

but to walk across the finish line."

Read the sign, well, maybe you can't make it out.

It reads, “The highest

wind ever observed by man was recorded here.” Paul continues:

"Once you finish, they give you a blanket and you have to park

you bike and get inside the summit restaurant to warm up. I was in

a

daze right after finishing and Hank [Schiffman] very kindly took

care of my bike for me."

Paul receives a medal on a ribbon. "The last

three times I've done this race, the weather has been benign. But when

I

first did it in 1999, it was sleeting and 35 degrees at the top. The

winds were only 20–30 mph and less dangerous, but they made it brutally

cold. It was not as cold this year, but I still rate this year's weather

as worse because of the danger of being blown off the side of the mountain."

Chris Chaput (at right) and family wait post-race atop the

mountain for the okay for cars to descend. His time was a very respectable

1:17.

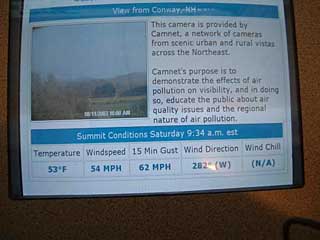

The wind speed on the monitor atop the mountain. Yes, those numbers are real.

Driving down post race. One can see the severity of

the grade.

Eats! Warmed up and back at the base of the mountain,

Paul tears into a drumstick at the post-event dinner.

A final word. Every participant in the Mt. Washington race has a story to tell, but there's also a story of those who didn't even make it to the start. John Zenkus dedicates his summer training to performing well on Mt. Washington. In fact it is hard to imagine anyone more devoted to the event. However August 16th he was not there. What happened? Put it down to The Blackout of 2003. Due to loss of communication between himself and other participants, Greg Cohen and Chris Taeger, rental car problems, gas lines and general confusion, the three of them found themselves stranded in New York City. One might imagine John getting on his bicycle and just riding up to the start, but no, even John Z has his limitations. However, one can already hear that siren song in the air, "next year . . . next year . . . " as John continues climbing our local hills.

|